Tags

Cloth, Herringbone, Houndstooth, Pattern, Pinstripe, Ropestripe, Sharkskin

Patterned suits can evoke two images, either that of the hapless nerd picking out a “snazzy” pattern to wear once a year at weddings, or of upper class gents donning tweeds and checks in which to stroll their grounds.

In reality pattern in suits is both common, useful and a good way to get creative without drawing too much attention. There are any number of patterns that you may come across so instead of decreeing rules to follow, I will simply name and describe some of the more coming patterns and how they might be utilised. If you find yourself unsure or lacking in confidence in their implementation, then I would advise you to avoid them; patterns could be seen as the second level of difficulty in suits – if they go wrong it is not the end of the world, but the errors are much more easily overlooked if the result of your wardrobe is impeccable.

Patterns can be roughly distributed between two categories, those that are created by using the same colour as the base fabric, but woven in a different way and those that are made up of a different colour all together woven into the cloth.

Weave- based patterns

Herringbone

A herringbone pattern is achieved when a weaver chooses to weave the warp and weft (the “up and down” threads and the “left to right” threads respectively) in such a way that half have a diagonal grain pointing one way and half that go in the other direction. The purpose of this is to create a subtle texture, often giving greater depth to the colour of the fabric. In many instances herringbone is subtle enough that many people will not even notice it.

Herringbone is easy enough to pair with shirts and ties; make sure that at least one item is of a bolder pattern and one item is less bold in pattern. My advice is normally to look at herringbone fabrics in blues, as greys can occasionally feel a little worn down with too much texture.

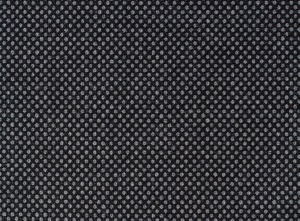

Birdseye

This fabric has such a subtle diamond shaped weave that tailors will not call it patterned, but for our purposes we can consider it so. In this fabric the edge of the diamond shape is woven in one direction and the centre in another to give a very subtle hint of texture. When picking out an outfit the cloth should be treated as a “solid” colour, and thus the patterns on your shirt and tie should not be influenced by the cloth.

Popular with the conservative crowd who wish to add a little detail to the outfit without going as far as a check or stripe, this fabric is also good for durability, as dust is more easily hidden in its textured surface. Naturally this is not an excuse the skip regular cleanings, but it helps if you must take dusty public transport to work.

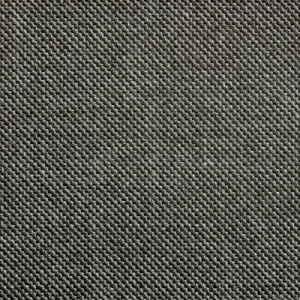

Sharkskin

This is a cloth that utilises a form of basket weave, so that a thread of dark grey or navy can run across one of a lighter shade. The effect of this weave is a two-tone one, but of subtle shades which result in depth and nuance rather than the green-blue two tone of the 90’s.

A wonderful choice for a more nuanced suit, one that looks elegant, but the reasons for which are not clear to the casual observer. You could compare a sharkskin cloth to a regular plain cloth with an analogy to gold and polished brass; from a distance they are the same, but the latter undoubtedly has more lustre and sheen than the former.

Sharkskin can be expensive, and hard to come by, but the reassurance is that I have never seen it produced at a low level, thus if you are considering such a cloth, there is a reasonable chance that the suit its self will be made to at least an acceptable standard.

Colour-based patterns

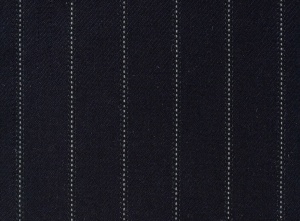

Pin stripe

The pin stripe can come in many different forms, from the subtle lines so fine as to be invisible, to the bold contrasting stripes of a “banker” suit.

Generally speaking pin stripes should be no more than one or two shades lighter than the cloth on which they are based, as the aim is to give texture and visual variance to the suit. I normally advice customers not to wear a stripe that is much wider than the nail on their index finger. The wider a stripe is set the less flattering it becomes, and the more distinctive the overall effect. While it is by no means unusual or wrong to wear a wider stipe, if you are reading this book for advice then there is a good chance that you won’t have the sartorial sense developed to do so without feeling self conscious.

I usually advise customers that a subtle pinstripe suit should be the third item into the new wardrobe, after a solid blue and solid grey. It is always best to look for cloths where the stripe is the same colour palette as the suit. It can be tempting to buy a blue suit with pink or purple pinstripes because it looks unique, but ultimately that is not a suit that will get worn and you are wasting money. As with all heavy patterns, follow the rule that “two out of three ain’t bad”, and only add in one more pattern to your ensemble.

Rope stripe

A rope stripe is similar to a pin stripe, except a touch thicker and with more texture to the stripe. If you look closely the stripe really does resemble a rope that has been woven through the fabric. This has an impact that is twofold; firstly the stipe can be thicker to increase its impact and secondly that the thick stripe has softer edges to ease the transition between the two colour.

A rope stripe can be difficult to pull off without looking “loud”. The archetypal image of a businessman in a blue rope striped suit, with contrasting white collars and cuffs and an enormous red tie is hard to escape.

If you wish to add this style to your wardrobe I would suggest finding it in a dark grey or navy blue flannel where the heavier fabric lends a softer air to the pattern.

Houndstooth

A hounds tooth pattern is a very small check, but instead of squares each block is in the shape of a cross (more accurately the shape of the cross section of a canine tooth). The “tooth” can be of any size, from just one or two threads wide to an inch across. The smaller the pattern the less distinctive and easier to work with, generally speaking.

More common in tweeds than worsted wools, the houndstooth pattern is a favourite of the more passionate tailors, but is often considered to be “showy” by less interested parties. In lighter colours the cloth can become very casual, a great favourite for garden parties or sporting events. I charcoal or navy it can be office appropriate, but like the rope stripe it can be too bold for conservative offices.